Why Ecology Expertise is Key for Robust MRV

As we explored in our recent article on how to assess the quality of nature data, creating highly accurate, audit-grade forest maps involves more than just satellite imagery. One of the most critical elements behind Space Intelligence’s ability to produce over 90% overall map accuracy is human insight – specifically, ecological expertise and local calibration.

In this article, we’ll walk through how and why our ecology team plays an important role in producing maps that meet the standards of nature data required to support VCM project origination and monitoring, and nature compliance reporting such as EUDR.

What Ecological Factors Influence Geospatial Mapping?

Uncalibrated global forest datasets can be a great starting point. But while these products cover the entire planet, they often rely on universal mapping classification models that aren’t equipped to deal with regional complexity. That’s not a flaw – it’s a limitation of scale.

What global products often miss are the ecological nuances: seasonal vegetation changes, region-specific land use patterns, and varying forest definitions. These differences matter when you’re making high-stakes decisions based on land cover data. Here’s what our ecologists look for when calibrating a map.

Seasonality

Deciduous forests shed their leaves during certain parts of the year. In the dry season, depending on when the satellite data was collected, that leaf loss can be misclassified as deforestation.

For example, Cambodia has extensive deciduous forest cover, and misclassifications in uncalibrated maps are common. These errors can lead to inflated deforestation alerts or missed regrowth events, both of which undermine confidence in the data and project performance.

Agriculture Practices

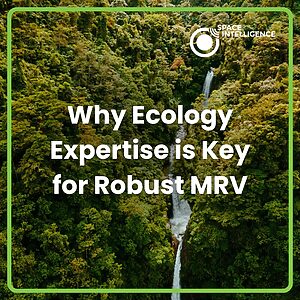

Agricultural land isn’t uniform. Coffee farms, for example, can look completely different depending on where they are.

In Brazil, coffee is typically grown in regimented rows, to make it easier to be harvested by machine – and relatively easy to identify from satellite imagery. In Kenya, coffee is picked by hand, so it is often intercropped and shaded by larger trees. In other countries, like Colombia and Ivory Coast, coffee and cocoa are surrounded by so many shaded trees, it’s hard to distinguish them from natural forest without local context.

Understanding these differences is particularly important for verifying data for compliance purposes, such as EUDR. It’s not enough to recognise a farm – you need to know what that farm looks like in that country.

Forest Definitions

What counts as a forest varies from one country to another. National definitions differ in terms of canopy cover, minimum area, and tree height. These definitions directly influence what gets classified as forest in REDD+ projects, particularly under certain Verra methodologies.

In Kenya, for example, forest is defined as an area of at least 0.5 hectares, with 15% canopy cover and with trees taller than 2 metres. That’s a far lower threshold than most global datasets assume, making it difficult to apply one-size-fits-all logic to land cover classification.

Our ecologists research each country’s Forest Reference Emission Level (FREL) and apply these national standards throughout the map-making process to ensure we meet the criteria of project methodologies.

The Role of the Ecologist Throughout the Mapping Process

At the Start: Area Reviews and Sample Collection

Before any mapping begins, the ecology team performs an in-depth area review. They study the country’s biomes, vegetation types, land use history, deforestation patterns, and relevant forest definitions.

From this foundation, ecologists create training samples for the model by manually drawing polygons around areas with known land cover types (like plantations, cropland, or open forest). These samples help the model learn how to classify pixels across the landscape.

During Mapping: Map Review and Local Calibration

Once the first iteration of the map is ready, ecologists review the map to identify and correct systematic errors. They also review change maps, which compare outputs from different time points. If a forested area suddenly appears as non-forest, but there’s no indication of change in the satellite imagery or the local ecology doesn’t support it, it’s likely a misclassification.

This process allows us to feed specific corrections back to the data science team, which improves the model’s performance in the next iteration.

At the End: Accuracy Assessment

Ecologists conduct independent accuracy assessments using high-resolution imagery. These assessments involve manually labeling validation points that are entirely separate from the training data. These manually labelled points are then compared to the same points on the new map, producing User’s and Producer’s Accuracy metrics, from which we derive our Overall Accuracy.

In projects with strict accuracy requirements, we also work with in-country partners who conduct parallel assessments. We compare results and resolve any disagreements through consensus, ensuring both parties agree on the final classification.

How Local Calibration Impacts Data Integrity

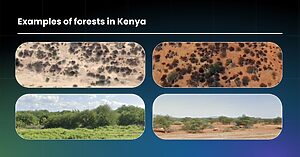

Let’s return to Cambodia to illustrate the impact of local calibration.

Here’s a comparison between two 2020 forest/non-forest maps of the country. The map on the left was generated by Global Forest Watch. The one on the right is ours.

Our map shows far less forest cover – because unfortunately, Cambodia has experienced extensive deforestation, particularly due to conversion of natural forest to tree plantations.

Because tree plantations appear as forest canopy from above, global datasets correctly predicted the same level of tree cover, but failed to account for land use change. GFW missed about 20% of deforestation between 2013 and 2022. That’s not a small margin – it’s the kind of error that can put a forest conservation project at significant financial and reputational risk. Without local ecological knowledge, including understanding of plantation types and seasonal variability, these misclassifications could go unnoticed and project efficacy questioned.

In Summary

High integrity forest carbon projects are nuanced – and ecological expertise and local calibration ensure that nuance is accounted for. If you want data to support forest projects or compliance with confidence, you can’t afford to rely solely on global, uncalibrated datasets.

At Space Intelligence, our ecology team is involved at every stage of map development, from research and sampling to map review and accuracy validation. Their work ensures that what we call “forest” on the map reflects the forest on the ground.

Need accurate forest data to support origination or impact assessment? Get in touch with our team.

Tag:accuracy, ecology, local calibration, mrv