How opportunity maps can help save the natural world and contribute to the net zero race

Space Intelligence co-founders Ed Mitchard and Murray Collins walking in peatland

How opportunity maps can help save the natural world and contribute to the net zero race

Many of Scotland’s landscapes, whilst considered wild, are in reality degraded ecosystems harbouring huge potential for restoration. By using satellite data, we can create ‘opportunity’ maps, defining the areas where restoration money will make the biggest difference. Restoring landscapes is beneficial not only for biodiversity, but also for Scotland to meet its target of net zero carbon by 2045, and the UK by 2050, making such work a key green and economic topic.

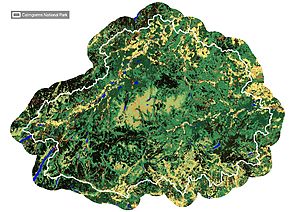

Using the power of opportunity maps, work is underway to bring the Cairngorms national park closer to its pre-industrial state. Old maps tell the tale of disappeared forests in the Cairngorms, which have Gaelic place names like “Allt na Da Chraobh Bheath” which means “Stream of the two birch trees”, in areas where no forest remains. Cairngorms Connect is a restoration project looking to improve the area’s carbon storage and protect habitats, as well as create jobs, encourage tourism and change attitudes towards how Scotland’s landscape is ‘meant’ to look.

The programme has been a big success story. Thanks to opportunity maps for woodland restoration, and the cooperation of landowners, Cairngorms’ trees are returning to the hills: this national park alone is meeting about 10% of Scotland’s tree planting targets.

There are many more restoration opportunities for Scotland waiting in the wings. Scotland has many rich, expansive peatlands such as the ‘Flow Country’ in Caithness and Sutherland – Europe’s largest expanse of blanket bog at over 400,000 ha. While these landscapes may look barren, they store more carbon per hectare than any forest.

Yet, many peatland areas are becoming degraded due to the draining of the land for plantations – when the bog dries out, it releases its carbon to the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

If we catch these degrading bogs before it is too late, we can block drainage ditches and repair areas of erosion, allowing them to again become waterlogged, and prevent further loss of carbon and habitat. But it’s a one-way street if we wait too long, and these bogs are destroyed – unlike the replanting of forests, which can be happen relatively quickly, peatland bogs tend to build up at a rate of 1mm per year, or 1m per millennium. So for practical purposes in our modern day fight against climate change, once these habitats are lost, they are lost for good.

Prioritisation is key: we need to identify the opportunities where peatland restoration is most urgent and will make the biggest impact. Space Intelligence is developing tools to identify areas of restoration priority from satellite imagery. We’ve recently been awarded £60,000 by Innovate UK to develop a proof-of-concept peatland health and opportunity mapping system, which you can read more about here.

It’s an exciting time, when satellite data, specialist analysts and AI combine to tell us the most cost effective way to save our wild spaces. That way we can save as much of it as possible, before it is lost, potentially forever.