The AI revolution in satellite data explained

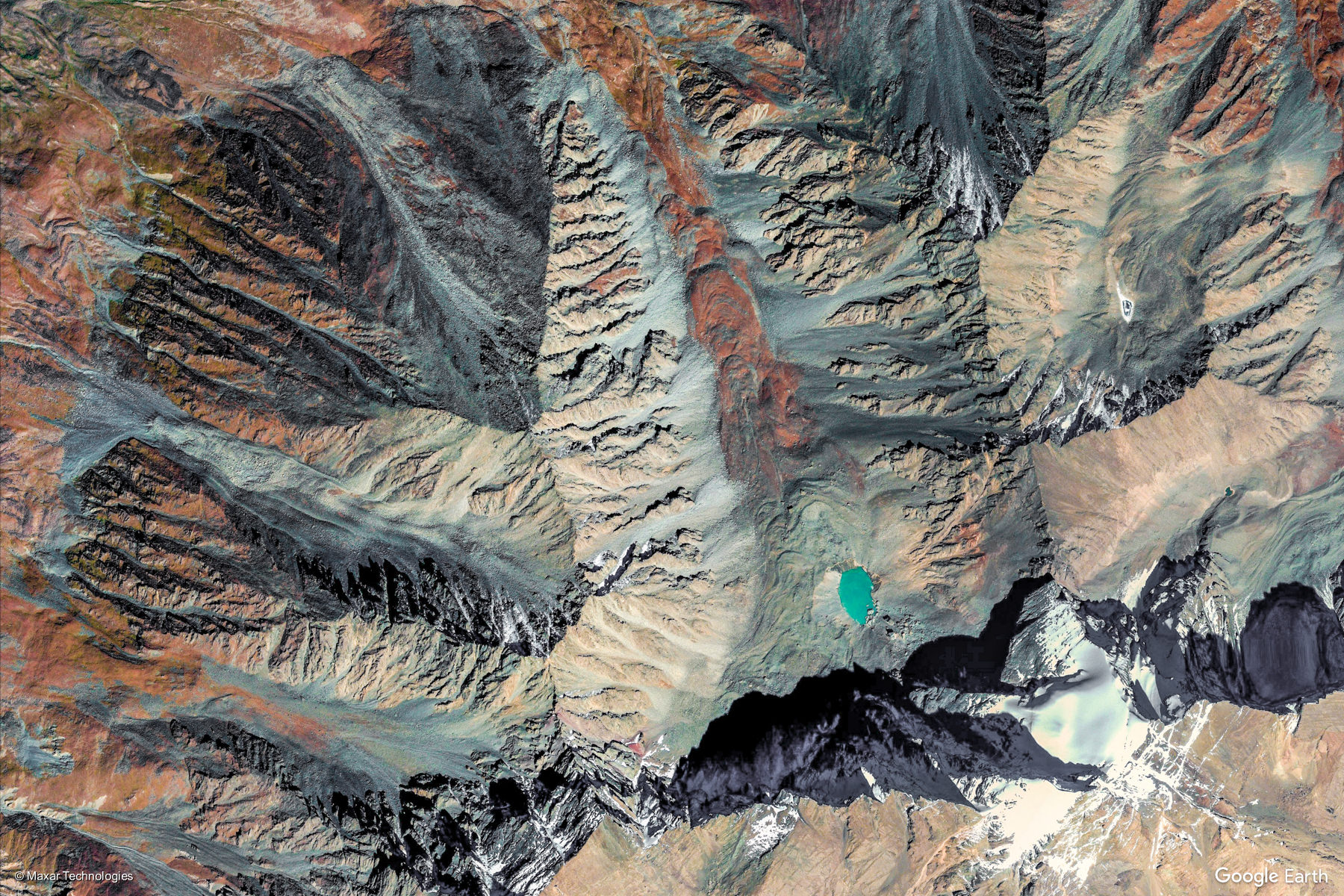

Looks like art? It’s actually a satellite view of Xigaze, China from a Worldview satellite at sub-meter resolution, captured from Google Earth. © 2020 Maxar Technologies

The AI revolution in satellite data explained

Not long ago, satellite data was all low resolution, with anything medium to high resolution sitting behind eye-wateringly expensive paywalls. Even when you got hold of it, datasets were so large that meaningful analyses with affordable computers took too long for most purposes. It was the preserve of governments (especially military department) and the world’s richest companies. Yet today, there are tens of terabytes of high-resolution, free and open data released every day, which can be probed with much more accessible hardware, or even in the cloud.

Access used to be so exclusive because governments aimed to make back money from their investments in satellites by charging companies, but this didn’t work well as uptake was low – the main clients were defence companies, which were mostly government funded in the first place. But this all changed in 2008 when the Obama administration released the Landsat archive to the world – the philosophy being that open data would generate economic growth and stimulate new business. This has proved to be the case – the United States Geological Survey calculates that free access to landsat was bringing domestic and international economic benefits to society totalling $2.19bn in 2011, increasing to $3.45bn in 2017.

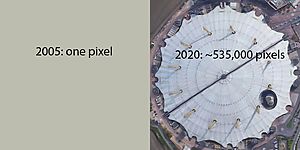

In the mid-2000s, the only free data had a best resolution of 250x250m pixels (about six football fields per pixel) – far too coarse to give useful intelligence about deforestation, carbon storage, or to map anything. Imagine a map of a city with pixel units of 250x250m – the Millennium Dome wouldn’t even stretch to two pixels, let alone being able to show any roads! Constant technological innovation means that today, the industry leading resolution is 41x41cm pixels, meaning that a maximum-resolution satellite image of the Millennium Dome today would comprise over half a million pixels.

© Google Earth

While these policy and technological developments began a revolution, in particular helping scientists add remote sensing to their research of an area without adding massive costs, the benefits didn’t immediately flow to companies and public goods, as it took a little while for data infrastructure and AI to catch up and harness the power of the data on offer.

Cloud computing capacity increased massively in the past 15 years, and prices have tumbled, meaning that analysing whole satellite archives is now possible. Google, Amazon and others invested in putting whole satellite archives nicely pre-processed on their servers, leading to services like Google Earth Engine. These have led to some fantastic outputs, like Global Forest Watch – which tracks all of the Earth’s forests annually using satellite data. You can explore their latest data on the health of the Earth’s forests here.

Some companies, including Space Intelligence, have been established to harness the potentials of applying powerful machine learning/AI systems to massive stacks of data. Combined with the cutting edge knowhow of our analysts, we can map carbon stocks and landcover globally at a historically low cost. There are countless other applications for combining AI and satellite data – some we’re working on, and many of which won’t have been thought of yet.

To help find those big new ideas, Space Intelligence are supporting SENSE, a new Centre for Doctoral Training in the UK, which has just welcomed its first students. The centre will train 50 PhD students from physical science and industry backgrounds in applying advanced data science techniques onto satellite datasets to solve global environmental problems. We at Space Intelligence will be co-funding two of the students, who will spend 3 months of their training embedded in our company, and will stay in touch with us throughout their four years. We hope to tell you how their work is getting on in a future post!

Some of the first PhD students at SENSE, meeting with their tutors, including Space Intelligence’s Ed Mitchard.