Detecting past deforestation and woody encroachment in a protected area in Ghana

A recent paper by Thomas Janssen, a PhD student at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, uses remote sensing to tell the story of the Kogyae Strict Nature Reserve in Ghana. The paper, co-authored by Space Intelligence’s Murray Collins and Edward Mitchard, reports major deforestation inside what is on paper a ‘strictly protected area’. The findings have implications for protected area management, and the use of remote sensing analysis to provide intelligence for landscape managers.

Introducing Kogyae

The Kogyae Strict Nature Reserve (KSNR) is one of the so called “barrier reserves”, established by the government of Ghana in the 1960s. The principle function of the reserve was to act as a barrier against wildfires spreading from the savanna in the north of the country towards the south. The reserve is positioned on the forest-savanna transition zone, with tropical dry forest and savanna occurring in close proximity, hence representing a hotspot of species and structural diversity. As such, the KSNR has attracted the attention of scientists studying the effect of fires, soils and water availability on the species composition, vegetation structure and ecosystem functioning in tropical forest and savanna.

The forest-savanna transition

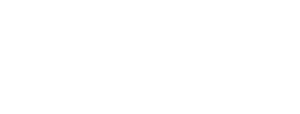

The question of why tall forest and open savanna can co-occur within a few hundred metres, is still hotly debated. Remote sensing can help to answer this and other related questions because it offers a way to assess the stability of forest and savanna vegetation by looking at decades of change in tree cover over inaccessible regions.

In the Kogyae Strict Nature Reserve, locations only a few hundred meters from each other showing very different “vegetation structural forms” from open savanna to closed woodland and forest.

Field data related to satellite imagery

Using a simple tape measure and a fisheye lens attached to a camera, Janssen estimated the area covered by crowns (crown area index) and the area covered by leaves (leaf area index) inside thirty-nine vegetation plots located in the reserve. These two measures of tree cover were then linked to the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) derived from a recent Landsat satellite image. The NDVI is calculated using the relative reflectance of near-infrared light and red light from the Earth’s surface. This means that the index is sensitive to vegetation greenness. The field measurements of tree cover agreed well with the NDVI data from a recent Landsat image, suggesting that a time series of NDVI data would be a useful method to detect changes in tree cover in the study area.

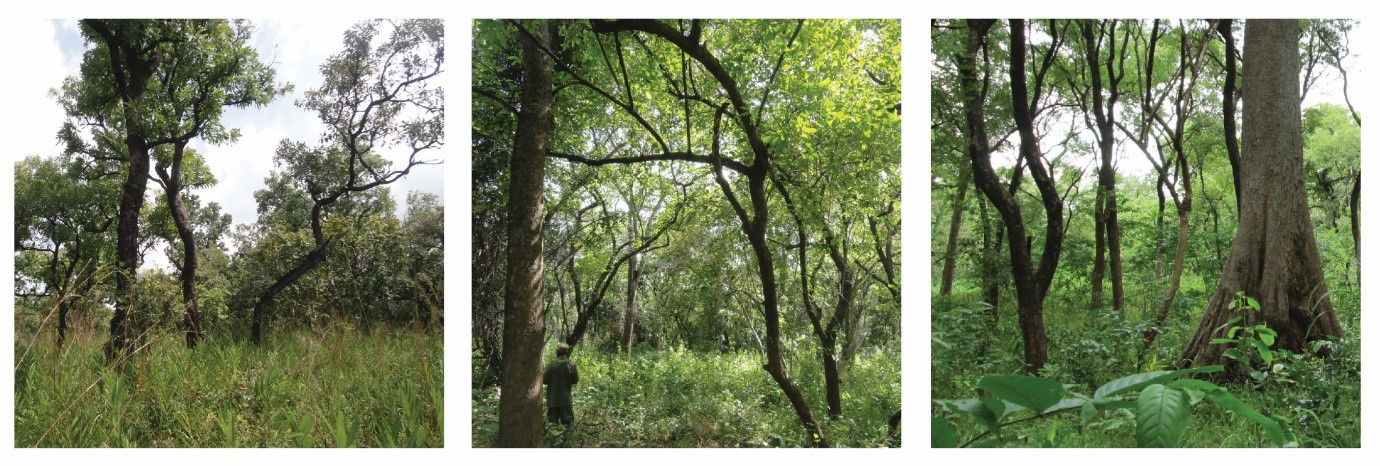

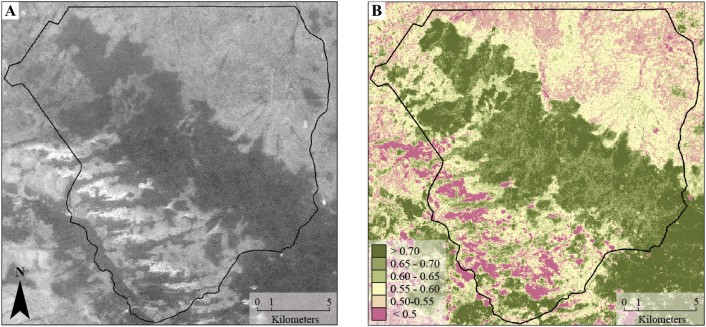

A Corona satellite photograph captured in January 1966 (A) and a Landsat 5 NDVI image from November 1984 (B) provide an indication of the initial vegetation cover inside Kogyae. The dry semi-deciduous forest is visible as darker colors in the Corona photograph and as high NDVI (> 0.6) in the Landsat image. The savanna is visible as greyish colors in the Corona photograph (NDVI 0.5–0.6). The boundary between the forest and savanna is abrupt, accentuated by annual fires that generally extinguish at the forest edge.

Analysis indicates large scale deforestation

The initial vegetation cover inside the reserve, with a large tract of natural forest extending into the savanna is clearly visible on old satellite images from the 1960s and 1980s. However, in more recent satellite images and aerial photographs, this forest has largely disappeared. Jannsen compared the changes in NDVI in three time steps from 1984 to 2015: significant declines in NDVI are visible from 1990 to 2002 in the area previously covered by forest, indicating major deforestation. Independent reports published in the 1990s already warned about the high deforestation rate as a result of agricultural expansion, and the authors of those articles feared for the complete loss of natural forest inside the KSNR. By the time the reserve management started to expel the agricultural communities residing inside the reserve in 2002, much of the original forest inside the KSNR had disappeared.

After abandonment of the agricultural fields, the area previously covered by forest changed into a treeless grassland. However, at the edges of the remaining forest patches there are signs of forest recovery.

The fragmented patches of forest are vulnerable to the fires that are lit intentionally every year both by the reserve management to provide fresh grass for grazing wildlife; and by poachers to flush out those same animals. Annual fires resulted in further forest degradation and forest loss between 2002 and 2015.

Management implications

The lighting of fires is therefore in direct contradiction with the initial aim of the reserve’s establishment, to maintain a forest barrier in the forest-savanna transition zone. Janssen therefore urges the reserve management to reconsider the deliberate burning practice as it hinders the recovery of forest inside the reserve.

Standard deviations of change in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) from 1984 to 2015. Using the standard deviation of change, only the areas that experienced significant change in NDVI are detected.

Hope for the future of Kogyae

On a happier note, Janssen also found that the fire-tolerant savanna inside the reserve has “greened-up” from 2002 to 2015, indicating that tree cover in the savanna has recently increased (also known in the research literature as ‘woody encroachment’. This observation of woody encroachment is in line with previous observations in Africa and South-America. The drivers of such encroachment are uncertain, one possibility is that the increased CO2 concentration in the atmosphere results in a more water efficient photosynthesis by plants. Reducing the loss of water during photosynthesis results in more water being available for plant growth and tree regeneration. If permitted, the process of forest regrowth could potentially bring back Kogyae’s forest in the future.

Generalising the work

The combination of field observations and remote sensing data has again proven to be useful for mapping tree cover and changes within it over large and inaccessible areas. The work once again highlights how formal de jure land status (e.g. strictly protected areas) can be entirely at odds with de facto land management and status (in this case forest conversion to agriculture between 1990 and 2002). Remote sensing analysis can also assist in the formulation of future management goals, by indicating areas of forest recovery or areas that are still vulnerable to forest degradation and deforestation.

Reference

Janssen, T.A., Ametsitsi, G.K., Collins, M., Adu-Bredu, S., Oliveras, I., Mitchard, E.T. and Veenendaal, E.M., 2018. Extending the baseline of tropical dry forest loss in Ghana (1984–2015) reveals drivers of major deforestation inside a protected area. Biological Conservation, 218, pp.163-172.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.12.004